Description

Ratanakiri (Khmer: ß×Üß×Åß×ōß×éß×Ęß×Üß×Ė IPA: [╦īre╔Ö╠»╠å╩ö ta╩ö ╦łna╩ö ki ╦łri╦É]) is a province (khaet) of Cambodia located in the remote northeast. It borders the provinces of Mondulkiri to the south and Stung Treng to the west and the countries of Laos and Vietnam to the north and east, respectively. The province extends from the mountains of the Annamite Range in the north, across a hilly plateau between the Tonle San and Tonle Srepok rivers, to tropical deciduous forests in the south. In recent years, logging and mining have scarred Ratanakiri's environment, long known for its beauty.

For over a millennium, Ratanakiri has been occupied by the highland Khmer Loeu people, who are a minority elsewhere in Cambodia. During the region's early history, its Khmer Loeu inhabitants were exploited as slaves by neighboring empires. The slave trade economy ended during the French colonial era, but a harsh Khmerization campaign after Cambodia's independence again threatened the Khmer Loeu ways of life. The Khmer Rouge built its headquarters in the province in the 1960s, and bombing during the Vietnam War devastated the region. Today, rapid development in the province is altering traditional ways of life.

Ratanakiri is sparsely populated; its 150,000 residents make up just over 1% of the country's total population. Residents generally live in villages of 20 to 60 families and engage in subsistence shifting agriculture. Ratanakiri is among the least developed provinces of Cambodia. Its infrastructure is poor, and the local government is weak. Health indicators in Ratanakiri are extremely poor; men's life expectancy is 39 years, and women's is 43 years. Education levels are also low, with just under half of the population illiterate.

Demographics and towns

As of 2013, Ratanakiri Province had a population of approximately 184,000. Its population nearly doubled between 1998 and 2013, largely due to internal migration. In 2013, Ratanakiri made up 1.3% of Cambodia's total population; its population density of 17.0 residents per square kilometer was just over one fifth the national average. About 70% of the province's population lives in the highlands; of the other 30%, approximately half live in more urbanized towns, and half live along rivers and in the lowlands, where they practice wetland rice cultivation and engage in market activities. Banlung, the provincial capital located in the central highlands, is by far the province's largest town, with a population of approximately 25,000. Other significant towns include Veun Sai in the north and Lomphat in the south, with populations of 2,000 and 3,000 respectively.

In 2013, 37% of Ratanakiri residents were under age 15, 52% were age 15 to 49, 7% were age 50 to 64, and 3% were aged 65 or older; 49.7% of residents were male, and 50.3% were female. Each household had an average of 4.9 members, and most households (85.6%) were headed by men.

While highland peoples have inhabited Ratanakiri for well over a millennium, lowland peoples have migrated to the province in the last 200 years. As of 2013, various highland groups collectively called Khmer Loeu made up approximately half of Ratanakiri's population, ethnic Khmers made up 36%, and ethnic Lao made up 10%. Within the Khmer Loeu population, 35% were Tampuan as of 1998, 24% were Jarai, 23% were Kreung, 11% were Brou, 3% were Kachok, and 3% were Kavet, with other groups making up the remaining one percent. There are also very small Vietnamese, Cham, and Chinese minorities. Though the official language of Ratanakiri (like all of Cambodia) is Khmer, each indigenous group speaks its own language. Less than 10% of Ratanakiri's indigenous population can speak Khmer fluently.

Economy and transportation

The vast majority of workers in Ratanakiri are employed in agriculture. Most of the indigenous residents of Ratanakiri are subsistence farmers, practicing slash and burn shifting cultivation. (See Culture below for more information on traditional subsistence practices.) Many families are beginning to shift production to cash crops such as cashews, mangoes, and tobacco, a trend that has accelerated in recent years. Ratanakiri villagers have traditionally had little contact with the cash economy. Barter exchange remains widespread, and Khmer Loeu villagers tended to visit markets only once per year until quite recently. As of 2005, monetary income in the province averaged US$5 per month per person; purchased possessions such as motorcycles, televisions, and karaoke sets have become extremely desirable.

Larger-scale agriculture occurs on rubber and cashew plantations. Other economic activities in the province include gem mining and commercial logging. The most abundant gem in Ratanakiri is blue zircon. Small quantities of amethyst, peridot, and black opal are also produced. Gems are generally mined using traditional methods, with individuals digging holes and tunnels and manually removing the gems; recently, however, commercial mining operations have been moving into the province. Logging, particularly illegal logging, has been a problem both for environmental reasons and because of land alienation. This illegal logging has been undertaken by the Cambodian military and by Vietnamese loggers. In 1997, an estimated 300,000 cubic meters of logs were exported illegally from Ratanakiri to Vietnam, compared to a legal limit of 36,000 cubic meters. John Dennis, a researcher for the Asian Development Bank, described the logging in Ratanakiri as a "human rights emergency".

Ratanakiri's tourist industry has rapidly expanded in recent years: visits to the province increased from 6,000 in 2002 to 105,000 in 2008 and 118,000 in 2011. The region's tourism development strategy focuses on encouraging ecotourism. Increasing tourism in Ratanakiri has been problematic because local communities receive very little income from tourism and because guides sometimes bring tourists to villages without residents' consent, disrupting traditional ways of life. A few initiatives have sought to address these issues: a provincial tourism steering committee aims to ensure that tourism is non-destructive, and some programs provide English and tourism skills to indigenous people.

Ox-cart and motorcycle are common means of transportation in Ratanakiri. The provincial road system is better than in some parts of the country, but remains in somewhat bad condition. National Road 78 between Banlung and the Vietnam border was built between 2007 and 2010; the road was expected to increase trade between Cambodia and Vietnam. There is a small airport in Banlung, but commercial flights to Ratanakiri have long been discontinued.

History

Present-day Ratanakiri has been occupied since at least the Stone or Bronze Age, and trade between the region's highlanders and towns along the Gulf of Thailand dates to at least the 4th century A.D. The region was invaded by Annamites, the Cham, the Khmer, and the Thai during its early history, but no empire ever brought the area under centralized control. From the 13th century or earlier until the 19th century, highland villages were often raided by Khmer, Lao, and Thai slave traders. The region was conquered by local Laotian rulers in the 18th century and then by the Thai in the 19th century. The area was incorporated into French Indochina in 1893, and colonial rule replaced slave trading. The French built huge rubber plantations, especially in Labansiek (present-day Banlung); indigenous workers were used for construction and rubber harvesting.

While under French control, the land comprising present-day Ratanakiri was transferred from Siam (Thailand) to Laos and then to Cambodia. Although highland groups initially resisted their colonial rulers, by the end of the colonial era in 1953 they had been subdued.

Ratanakiri Province was created in 1959 from land that had been the eastern area of Stung Treng Province. The name Ratanakiri (ß×Üß×Åß×ōß×éß×Ęß×Üß×Ė) is formed from the Khmer words ß×Üß×Åß×ōߤł (ratana "gem" from Sanskrit ratna) and ß×éß×Ęß×Üß×Ė (kiri "mountain" from Sanskrit giri), describing two features for which the province is known. During the 1950s and 1960s, Norodom Sihanouk instituted a development and Khmerization campaign in northeast Cambodia that was designed to bring villages under government control, limit the influence of insurgents in the area, and "modernize" indigenous communities. Some Khmer Loeu were forcibly moved to the lowlands to be educated in Khmer language and culture, ethnic Khmer from elsewhere in Cambodia were moved into the province, and roads and large rubber plantations were built. After facing harsh working conditions and sometimes involuntary labor on the plantations many Khmer Loeu left their traditional homes and moved farther from provincial towns. In 1968, tensions led to an uprising by the Brao in which several Khmer were killed. The government responded harshly, torching settlements and killing hundreds of villagers.

In the 1960s, the ascendant Khmer Rouge forged an alliance with ethnic minorities in Ratanakiri, exploiting Khmer Loeu resentment of the central government. The Communist Party of Kampuchea headquarters was moved to Ratanakiri in 1966, and hundreds of Khmer Loeu joined CPK units.

During this period, there was also extensive Vietnamese activity in Ratanakiri. Vietnamese communists had operated in Ratanakiri since the 1940s; at a June 1969 press conference, Sihanouk said that Ratanakiri was "practically North Vietnamese territory". Between March 1969 and May 1970, the United States undertook a massive covert bombing campaign in the region, aiming to disrupt sanctuaries for communist Vietnamese troops. Villagers were forced outside of main towns to escape the bombings, foraging for food and living on the run with the Khmer Rouge. In June 1970, the central government withdrew its troops from Ratanakiri, abandoning the area to Khmer Rouge control. The Khmer Rouge regime, which had not initially been harsh in Ratanakiri, became increasingly oppressive. The Khmer Loeu was forbidden from speaking their native languages or practicing their traditional customs and religion, which were seen as incompatible with communism. Communal living became compulsory, and the province's few schools were closed. Purges of ethnic minorities increased in frequency, and thousands of refugees fled to Vietnam and Laos. Preliminary studies indicate that bodies accounting for approximately 5% of Ratanakiri's residents were deposited in mass graves, a significantly lower rate than elsewhere in Cambodia.

After the Vietnamese defeated the Khmer Rouge in 1979, government policy toward Ratanakiri became one of benign neglect. The Khmer Loeu were permitted to return to their traditional livelihoods, but the government provided little infrastructure in the province. Under the Vietnamese, there was little contact between the provincial government and many local communities. Long after the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime, however, Khmer Rouge rebels remained in the forests of Ratanakiri. Rebels largely surrendered their arms in the 1990s, though attacks along provincial roads continued until 2002.

Ratanakiri's recent history has been characterized by development and attendant challenges to traditional ways of life. The national government has built roads, encouraged tourism and agriculture, and facilitated rapid immigration of lowland Khmers into Ratanakiri. Road improvements and political stability have increased land prices, and land alienation in Ratanakiri has been a major problem. Despite a 2001 law allowing indigenous communities to obtain collective title to traditional lands, some villages have been left nearly landless. The national government has granted concessions over land traditionally possessed by Ratanakiri's indigenous peoples, and even land "sales" have often involved bribes to officials, coercion, threats, or misinformation. Following the involvement of several international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), land alienation had decreased in frequency as of 2006. In the 2000s, Ratanakiri also received hundreds of Degar (Montagnard) refugees fleeing unrest in neighboring Vietnam; the Cambodian government was criticized for its forcible repatriation of many refugees.

Geography and climate

Covering an area of 10,782 km2 (4,163 sq mi), the geography of Ratanakiri Province is diverse, encompassing rolling hills, mountains, plateaus, lowland watersheds, and crater lakes. Two major rivers, Tonle San and Tonle Srepok, flow from east to west across the province. The province is known for its lush forests; as of 1997, 70–80% of the province was forested, either with old-growth forest or with secondary forest re-grown after shifting cultivation. In the far north of the province are mountains of the Annamite Range; the area is characterized by dense broadleaf evergreen forests, relatively poor soil, and abundant wildlife. In the highlands between Tonle San and Tonle Srepok, the home of the vast majority of Ratanakiri's population, a hilly basalt plateau provides fertile red soils. Secondary forests dominate this region. South of the Srepok River is a flat area of tropical deciduous forests.

Like other areas of Cambodia, Ratanakiri has a monsoonal climate with a rainy season from June to October, a cool season from November to January, and a hot season from March to May. Ratanakiri tends to be cooler than elsewhere in Cambodia. The average daily high temperature in the province is 34.0 °C (93.2 °F), and the average daily low temperature is 22.1 °C (71.8 °F). Annual precipitation is approximately 2,200 millimeters (87 in). Flooding often occurs during the rainy season and has been exacerbated by the recently built Yali Falls Dam.

Flora & Fauna

Ratanakiri has some of the most biologically diverse lowland tropical rainforest and montane forest ecosystems in mainland Southeast Asia. One 1996 survey of two sites in Ratanakiri and one site in neighboring Mondulkiri recorded 44 mammal species, 76 bird species, and 9 reptile species. A 2007 survey of Ratanakiri's Virachey National Park recorded 30 ant species, 19 katydid species, 37 fish species, 35 reptile species, 26 amphibian species, and 15 mammal species, including several species never before observed. Wildlife in Ratanakiri includes Asian elephants, gaur, and monkeys. Ratanakiri is an important site for the conservation of endangered birds, including the giant ibis and the greater adjutant. The province's forests contain a wide variety of flora; one half-hectare forest inventory identified 189 species of trees and 320 species of ground flora and saplings.

Nearly half of Ratanakiri has been set aside in protected areas, which include Lomphat Wildlife Sanctuary and Virachey National Park. Even these protected areas, however, are subject to illegal logging, poaching, and mineral extraction. Though the province has been known for its relatively pristine environment, recent development has spawned environmental problems. The unspoiled image of the province often conflicts with the reality on the ground: visitors "expecting to find pristine forests teeming with wildlife are increasingly disappointed to find lifeless patches of freshly cut tree stumps". Land use patterns are changing as population growth has accelerated and agriculture and logging have intensified. Soil erosion is increasing, and microclimates are being altered. Habitat loss and unsustainable hunting have contributed to the province's decreasing biodiversity.

Culture

Khmer Loeu typically practices subsistence slash and burn shifting cultivation in small villages of between 20 and 60 nuclear families. Each village collectively owns and governs a forest territory whose boundaries are known though not marked. Within this land, each family is allocated, on average, 1–2 hectares (2.5–5 acres) of actively cultivated land and 5–6 hectares (12.5–15 acres) of fallow land. The ecologically sustainable cultivation cycle practiced by the Khmer Loeu generally lasts 10 to 15 years. Villagers supplement their agricultural livelihood with low-intensity hunting, fishing, and gathering over a large area.

Khmer Loeu diets in Ratanakiri are largely dictated by the food that is available for harvesting or gathering. Numerous food taboos also limit food choice, particularly among pregnant women, children, and the sick. The primary staple grain is rice, though most families experience rice shortages during the six months before harvest time. Some families have begun to plant maize to alleviate this problem; other sources of grain include potatoes, cassava, and taro. Most Khmer Loeu diets are low in protein, which is limited in availability. Wild game and fish are major protein sources, and smaller animals such as rats, wild chickens, and insects are also sometimes eaten. Domestic animals such as pigs, cows, and buffaloes are only eaten when sacrifices are made. In the rainy season, many varieties of vegetables and leaves are gathered from the forest. (Vegetables are generally not cultivated.) Commonly eaten fruits include bananas, jackfruit, papayas, and mangoes.

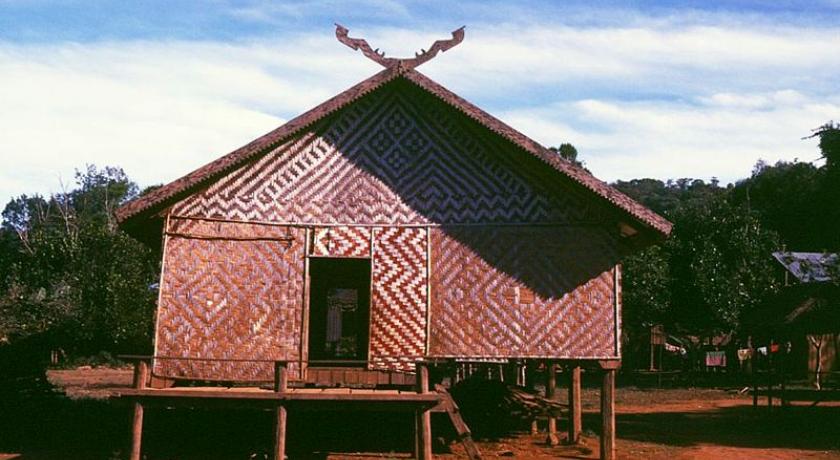

Houses in rural Ratanakiri are made from bamboo, rattan, wood, saek, and kanma leaves, all of which are collected from nearby forests; they typically last for around three years. Village spatial organization varies by ethnic group. Kreung villages are constructed in a circular manner, with houses facing inwards toward a central meeting house. In Jarai villages, vast longhouses are inhabited by all extended families, with the inner house divided into smaller compartments. Tampuan villages may follow either pattern.

Nearly all Khmer Loeu are animist, and their cosmologies are intertwined with the natural world. Some forests are believed to be inhabited by local spirits, and local taboos forbid cutting in those areas. Within spirit forests, certain natural features such as rock formations, waterfalls, pools, and vegetation are sacred. Major sacrificial festivals in Ratanakiri occur during March and April, when fields are selected and prepared for the new planting season. Christian missionaries are present in the province, and some Khmer Loeu have converted to Christianity. The region's ethnic Khmer are Buddhist. There is also a small Muslim community, consisting mainly of ethnic Cham.

Because of the province's high prevalence of malaria and its distance from regional centers, Ratanakiri was isolated from Western influences until the late 20th century. Major cultural shifts have occurred in recent years however, particularly in villages near roads and district towns; these changes have been attributed to contact with internal immigrants, government officials, and NGO workers. Clothing and diets are becoming more standardized, and traditional music is being displaced by Khmer music. Many villagers have also observed a loss of respect for elders and a growing divide between the young and the old. Young people have begun to refuse to abide by traditional rules and have stopped believing in spirits.

Tourism

See

Banlung, the capital of Ratanakiri District is situated near several spectacular natural attractions, including waterfalls, lakes and natural parks, and has hill tribe villages.

- Yeak Laom Volcanic Lake. A 700,000 year old volcanic crater lake in the Yeak Laom (Yaklom) Commune Protected Area. The lake itself, as well as the surrounding areas, are considered sacred by the local tribal minorities, and many a legend abound about this lake. There are docks on the lake, and swimming and picnicking are options here. There is also a hiking trail which winds around the lake. Along the trail there is a visitor’s centre displaying some objects and folklore of the local hill tribes. Very next to Crater Lake, there is a little village of Minoritie where you can see them sew (minority style) Cambodian scarfs. They even grow their own cotton. 8,000 riel (US$2).

- Wat Rahtanharahm. Located about 1 kilometre out of town at the base of Eisey Patamak Mountain. Past the Wat and up the hill about half a kilometre is a large reclining Buddha with a spectacular view of the surrounding countryside.

- Waterfalls. There are several local waterfalls, and they are best seen during the rainy season when the water volume is at its highest and the vegetation is lush and green. Cha Ong is the most toured waterfall in the area, and is 18 metres high. The rock area behind the waterfall has been eroded away over the centuries by the waterfall, thus allowing you to walk behind the fall. Kan Chang is another fall, this one approximately 7 metres in height. It empties into a large pool in which it is possible to swim. Ka Tieng is a third waterfall, this one 10 metres tall, in the jungle which also allows swimming. Further out from town are Ou'Sean Lair Waterfall (about 26 km SE) with 4 tiers, Ou'Sensranoh Waterfall (about 9 km SE and 18m high), Veal Rum Plan stone field (about 14 km N) and another crater lake (about 35km SE). Be careful when the roads are wet as they are extremely slick and slippery. Each waterfall charges a 2,000 riel entry fee with some an additional 1000 riel vehicle fee.

- Rubber Plantations. On the way to the waterfalls, there are a few large rubber plantations.

- Mining Tour. As you might have figured out from all the gem dealers in town, Banlung and the Ratanakiri province is a significant gem mining area. Miners work in the Bokeo mines about 36km from the town extracting the gems which sometimes end up for sale in Banlung's market. You can even buy directly at the gem mine where they extracting the gem.

- Virachey National Park, (37km northeast of town and borders Laos and Vietnam). Its chock full of jungle and mountains, and hasn't been completely explored yet. In the wet season, not all areas of the park are accessible. The Ministry of Environment (Biodiversity and Protected Areas Management Project) offers jungle treks into the park, guided by a park ranger and community guide. Their office is located near the center of Banlung.

- Banlung's market, Phsar Banlung, is a typical Cambodian market selling the same merchandise as other markets. At early many Khmer Loeu people come to the market from their villages to sell fruits, vegetables and forest products. In addition to offering a good shopping opportunity it is a very photogenic, although permission should be sought. Because the forest next to the city, you can find dear, wild boar, snake, lizard...

Note: Respect the locals. Ethnic minorities are animist and many taboos exist. At certain times (e.g. village sacrifice ceremonies), outsiders are prohibited to enter the village. Look out for some signs (such as fresh tree leaves hanging in front of the village gate or house). Taking pictures of people or places in hill tribe villages can break a taboo or disturb the spirits so get permission - you may be fined if you don't. If you are unsure about local traditions, do not enter villages without a knowledgeable guide.

Sleep

There are many hotels, bungalow lodges and numerous guest houses in and around town.

Eat

Eat responsibly in Banlung and don't encourage poaching by eating the local wildlife.

There's not much to differentiate Banlung cuisine from other Cambodian towns. All but three restaurants are owned and run by Cambodians. Aside from restaurants located in guest houses, there are several eateries that serve western food. All of these serve a variety of Cambodian and Western food and drinks, the staff are very friendly and dishes start at around US$1.50 or R6000:

Drink

South of the roundabout are four shops selling beer, wine and spirits, all a bit more expensive than more accessible places like Phnom Penh. The range of wines is modest; buffs would do well to bring a stock.

All the restaurants and most hotels and lodges have bar service, with A'Dam and Gecko offering draft beer.

East of the market is the Apocalypse bar, with quiet atmosphere and western music.

Bar at the Motel Phnom Yaklom, Banlung, Ratanakiri (call for a ride.), ŌśÄ 0978160345,. The restaurant at the Motel Phnom Yaklom is starting to attract travelers for sunset drinks. It's on top of a hill and has beautiful views all day, but especially sunset. Call them and they'll drive you up the hill for free from your guesthouse and drive you back.

Get around

The best way to get around Ratanakiri is by motorcycle, either by renting one and then driving it yourself, or by hiring one of the ubiquitous motodop drivers hanging all around town. Be mindful of the fact that almost no one outside the town will speak English, so it may be a good idea to hire a guide to go with you to some of the villages.

You can possibly rent bicycles near the roundabout. Sometimes they are sold out, and one shop is quite stern about taking passports as a deposit.

You can also rent trucks or 4 wheel drive vehicles if you'd like, but the cost (US$30-50/day) is often quite prohibitive to drive yourself. However, renting a car with a driver is usually helpful. This rent can be organized by various hotels and restaurants, and at Parrot tours. For bigger groups Dutch Co & Co and Terres Rouges lodge rent a Landcruiser with driver/guide which can carry up to 8 persons; a bit more expensive.

Most guest houses will arrange guides and these seem to get good reviews generally. A number of shopfront tour shops have sprung up since early 2009.

Money & Banks

Acleda (pronounced "A.C. leader") is an bank in Banlung, and as of July 2010 it has an ATM which accepts Visa but not Cirrus or Mastercard facilities. Since guesthouses in town that cash travellers' cheques charge high commissions and ATMs are unreliable visitors are advised to carry sufficient cash both for the visit and for travel onto the next destination. (Note: the Acleda charge for overseas cards is $US2, and although many Cambodian banks in Phnom Penh don't charge, ANZ Royal charge $4.)

Canadia Bank have just (Jun 2012) opened a branch with a 24-hr ATM (that takes all cards) on the street on the west side of the market.

Get in

By bus

Road Conditions: The road between Phnom Penh and Stung Treng is not very good. The road between the Stung Treng junction and Banlung is fully sealed.

It is possible to get buses to Banlung from/to:

Phnom Penh - Doing this in a single day is now reliable, with 3 'big' buses (Rithmony, Hy Long, GST; R39,000/$9.70) and numerous minivans (R72,000/$18) servicing the route regularly, departing from 6 - 7:30am. The minivans are faster but the free pickup and drop-off can add 2-3 hours to the 8 hour trip.

Kratie - Two options currently (2012-04):

Shared minibus. Leaves around 8am, takes 5-6 hours. Costs $8. Beware that they seat 4 people in each row of 3 seats, so it can be packed.

Phnom Penh Soraya Transport bus. Leaves 12:30pm. Takes 5-7 hours. Costs $8. Buses are often late.

Sen Monorom - As of March 2015, the road between Banlung and Sen Monorom is still under construction. It is currently a good dirt track, a bit bumpy in some parts. Minivans now operate between the two cities.

Stung Treng - You can get a Minibus for $7 at the riverside, takes about 2 ½ hours, departure is as 7:30 in the morning

Laos- It is possible to buy a ticket to Four Thousand Islands in Laos from Banlung. These are not direct buses; you must take three buses, switching at Stung Treng and at the border, and then a boat to your final destination. Costs $14-18. Despite what you may be told at the Lao Embassy in Phnom Penh, Laos’s visas have been available on arrival at the border since about October 2009. The reverse trip - from Don Det to Banlung is NOT a full ticket and you will need to pay an additional $5 for a taxi to Banlung from an intersection just south of Stung Treng. You will be essentially dropped off in the middle of nowhere to fend for yourself. It's best to just buy a ticket from Don Det to Stung Treng (about 150,000 kip) and then arrange transport on your own to Banlung.

By private taxi

A more expensive option than bus, taking a private taxi from Phnom Penh to Banlung is possible, for about US$120. It's a 5-6 hour drive to the junction near Stung Treng, then 2 hours to Banlung, plus meal breaks. Some taxi drivers in Phnom Penh specialize in this trip. Your hotel/guesthouse will probably be able to help you out.

Vietnam. The border crossing O Yadaw (Cambodia) to Pleiku (Gia Lai Province) and Quy Nhon (Viet Nam) has been opened to foreign travellers. Vietnam visas are not available at the border but Cambodia visas are.

In Banlung, bus tickets are available for US $ 12 to Pleiku in Vietnam, a major city with onward connections. After the border you get a new, Vietnamese bus. All these buses are minibuses. No more improvisation is required as described for instance in Lonely Planet guides. The trip takes about four hours, including a lengthy stop at the border because the Vietnamese bus waits until it is full.

Alternatively from Pleiku town, take a public van (2 hours) or taxi (1 hour and 30 min) to the border. The Cambodia post is isolated with no regular transport. The immigration police may help find a taxi; bargain - up to $80 for a whole car or $30 for a motorbike with driver. 70 km; 2 1/2 hours. Highway #78 has been completed and is now one of the best roads in Cambodia.

Source https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ratanakiri_Province

http://wikitravel.org/en/Banlung

Address

Ratanakiri Province

Cambodia

Lat: 13.857660294 - Lng: 107.101196289