Description

Uluru (Pitjantjatjara: Uluß╣¤u), also known as Ayers Rock and officially gazetted as "Uluru / Ayers Rock", is a large sandstone rock formation in the southern part of the Northern Territory in central Australia. It lies 335 km (208 mi) south west of the nearest large town, Alice Springs, 450 km (280 mi) by road.

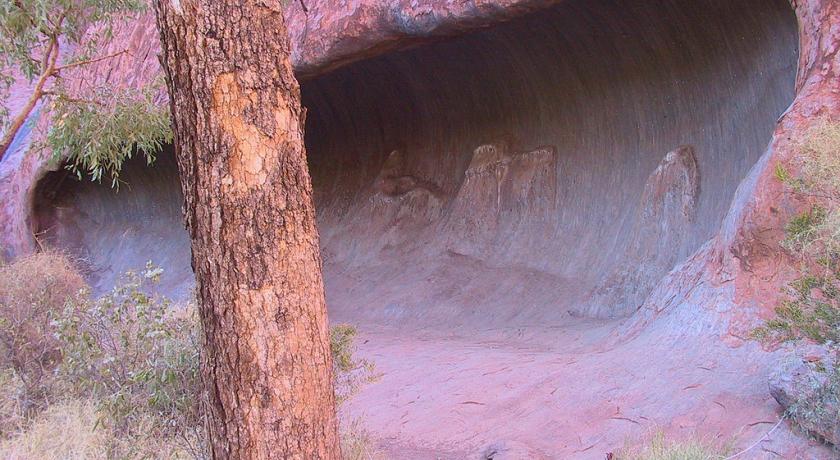

Uluru is sacred to the Pitjantjatjara Anangu, the Aboriginal people of the area. The area around the formation is home to an abundance of springs, waterholes, rock caves and ancient paintings. Uluru is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Uluru and Kata Tjuta, also known as the Olgas, are the two major features of the Uluß╣¤u-Kata Tjuß╣»a National Park.

This Park protects fragile species, adapted to the arid climate of the outback, and an important resource for the Anangu. It has become an attraction tourism flagship from the 1940s. This status has caused various reactions of the aborigines, especially when some of the 400,000 tourists who parade each year venture to climb the rock.

Name

The local Anangu, the Pitjantjatjara people, call the landmark Uluß╣¤u (Pitjantjatjara [ulu╔╗u]). This word is a proper noun, with no further particular meaning in the Pitjantjatjara dialect, although it is used as a local family name by the senior Traditional Owners of Uluru.

The underlined r in Uluß╣¤u represents a voiced retroflex spiral consonant used by some dialects of American English. However it is found to translate the words "protection" and "long sleep" or "journey" also used to define "freedom", in most languages ŌĆŗŌĆŗAnangu

On 19 July 1873, the surveyor William Gosse sighted the landmark and named it Ayers Rock in honour of the then Chief Secretary of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers. Since then, both names have been used.

In 1993, a dual naming policy was adopted that allowed official names that consist of both the traditional Aboriginal name and the English name. On 15 December 1993, it was renamed "Ayers Rock / Uluru" and became the first official dual-named feature in the Northern Territory. The order of the dual names was officially reversed to "Uluru / Ayers Rock" on 6 November 2002 following a request from the Regional Tourism Association in Alice Springs.

The aboriginal name is reported by Burke and Wills' expedition in 1903. Since then, both names are used indiscriminately, although Ayers Rock was mostly used by foreigners until recently.

Description

Uluru is one of Australia's most recognisable natural landmarks. The sandstone formation stands 348 m (1,142 ft) high, rising 863 m (2,831 ft) above sea level with most of its bulk lying underground, and has a total circumference of 9.4 km (5.8 mi). Both Uluru and the nearby Kata Tjuta formation have great cultural significance for the Aß╣ēangu people, the traditional inhabitants of the area, who lead walking tours to inform visitors about the local flora and fauna, bush food and the Aboriginal dreamtime stories of the area.

Uluru is notable for appearing to change colour at different times of the day and year, most notably when it glows red at dawn and sunset.

Kata Tjuta, also called Mount Olga or the Olgas, lies 25 km (16 mi) west of Uluru. Special viewing areas with road access and parking have been constructed to give tourists the best views of both sites at dawn and dusk.

Geology

Uluru is an inselberg, literally "island mountain". An inselberg is a prominent isolated residual knob or hill that rises abruptly from and is surrounded by extensive and relatively flat erosion lowlands in a hot, dry region. Uluru is also often referred to as a monolith, although this is a somewhat ambiguous term that is generally avoided by geologists. The remarkable feature of Uluru is its homogeneity and lack of jointing and parting at bedding surfaces, leading to the lack of development of scree slopes and soil. These characteristics led to its survival, while the surrounding rocks were eroded. For the purpose of mapping and describing the geological history of the area, geologists refer to the rock strata making up Uluru as the Mutitjulu Arkose, and it is one of many sedimentary formations filling the Amadeus Basin.

Composition

Uluru is dominantly composed of coarse-grained arkose (a type of sandstone characterized by an abundance of feldspar) and some conglomerate. Average composition is 50% feldspar, 25–35% quartz and up to 25% rock fragments; most feldspar is K-feldspar with only minor plagioclase as subrounded grains and highly altered inclusions within K-feldspar. The grains are typically 2–4 millimetres (0.079–0.157 in) in diameter, and are angular to subangular; the finer sandstone is well sorted, with sorting decreasing with increasing grain size. The rock fragments include subrounded basalt, invariably replaced to various degrees by chlorite and epidote. The minerals present suggest derivation from a predominantly granite source, similar to the Musgrave Block exposed to the south. When relatively fresh, the rock has a grey colour, but weathering of iron-bearing minerals by the process of oxidation gives the outer surface layer of rock a red-brown rusty colour. Features related to deposition of the sediment include cross-bedding and ripples, analysis of which indicated deposition from broad shallow high energy fluvial channels and sheet flooding, typical of alluvial fans.

Age and origin

The Mutitjulu Arkose is believed to be of about the same age as the conglomerate at Kata Tjuta, and to have a similar origin despite the rock type being different, but it is younger than the rocks exposed to the east at Mount Conner, and unrelated to them. The strata at Uluru are nearly vertical, dipping to the south west at 85°, and have an exposed thickness of at least 2,400 m (7,900 ft). The strata dip below the surrounding plain and no doubt extend well beyond Uluru in the subsurface, but the extent is not known.

The rock was originally sand, deposited as part of an extensive alluvial fan that extended out from the ancestors of the Musgrave, Mann and Petermann Ranges to the south and west, but separate from a nearby fan that deposited the sand, pebbles and cobbles that now make up Kata Tjuta.

The similar mineral composition of the Mutitjulu Arkose and the granite ranges to the south is now explained. The ancestors of the ranges to the south were once much larger than the eroded remnants we see today. They were thrust up during a mountain building episode referred to as the Petermann Orogeny that took place in late Neoproterozoic to early Cambrian times (550–530 Ma), and thus the Mutitjulu Arkose is believed to have been deposited at about the same time.

The arkose sandstone which makes up the formation is composed of grains that show little sorting based on grain size, exhibit very little rounding and the feldspars in the rock are relatively fresh in appearance. This lack of sorting and grain rounding is typical of arkosic sandstones and is indicative of relatively rapid erosion from the granites of the growing mountains to the south. The layers of sand were nearly horizontal when deposited, but were tilted to their near vertical position during a later episode of mountain building, possibly the Alice Springs Orogeny of Palaeozoic age (400–300 Ma).

Fauna and flora

Historically, 46 species of native mammals are known to have been living near Uluru; according to recent surveys there are currently 21. Aß╣ēangu acknowledge that a decrease in the number has implications for the condition and health of the landscape. Moves are supported for the reintroduction of locally extinct animals such as malleefowl, common brushtail possum, rufous hare-wallaby or mala, bilby, burrowing bettong, and the black-flanked rock-wallaby.

The mulgara, the only mammal listed as vulnerable, is mostly restricted to the transitional sand plain area, a narrow band of country that stretches from the vicinity of Uluru to the northern boundary of the park and into Ayers Rock Resort. This area also contains the marsupial mole, woma python, and great desert skink.

The bat population of the park comprises at least seven species that depend on day roosting sites within caves and crevices of Uluru and Kata Tjuta. Most of the bats forage for aerial prey within 100 m (330 ft) or so from the rock face. The park has a very rich reptile fauna of high conservation significance, with 73 species having been reliably recorded. Four species of frogs are abundant at the base of Uluru and Kata Tjuta following summer rains. The great desert skink is listed as vulnerable.

Aß╣ēangu continue to hunt and gather animal species in remote areas of the park and on Aß╣ēangu land elsewhere. Hunting is largely confined to the red kangaroo, bush turkey, emu, and lizards such as the sand goanna and perentie.

Of the 27 mammal species found in the park, six are introduced: the house mouse, camel, fox, cat, dog, and rabbit. These species are distributed throughout the park, but their densities are greatest near the rich water run-off areas of Uluru and Kata Tjuta.

Uluß╣¤u–Kata Tjuß╣»a National Park flora represents a large portion of plants found in Central Australia. A number of these species are considered rare and restricted in the park or the immediate region. Many rare and endemic plants are found in the park.

The growth and reproduction of plant communities rely on irregular rainfall. Some plants are able to survive fire and some are dependent on it to reproduce. Plants are an important part of Tjukurpa, and ceremonies are held for each of the major plant foods. Many plants are associated with ancestral beings.

Flora in Uluß╣¤u–Kata Tjuß╣»a National Park can be broken into these categories:

- Punu – trees

- Puti – shrubs

- Tjulpun-tjulpunpa – flowers

- Ukiri – grasses

Trees such as the mulga and centralian bloodwood are used to make tools such as spearheads, boomerangs, and bowls. The red sap of the bloodwood is used as a disinfectant and an inhalant for coughs and colds.

Several rare and endangered species are found in the park. Most of them, like adder's tongue ferns, are restricted to the moist areas at the base of the formation, which are areas of high visitor use and subject to erosion.

Since the first Europeans arrived, 34 exotic plant species have been recorded in the park, representing about 6.4% of the total park flora. Some, such as perennial buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris), were introduced to rehabilitate areas damaged by erosion. It is the most threatening weed in the park and has spread to invade water- and nutrient-rich drainage lines. A few others, such as burrgrass, were brought in accidentally, carried on cars and people.

Climate and five seasons

The park has a hot desert climate and receives an average rainfall of 284.6 mm (11.2 in) per year. The average high temperature in summer (December–January) is 37.8 °C (100.0 °F), and the average low temperature in winter (June–July) is 4.7 °C (40.5 °F). Temperature extremes in the park have been recorded at 46 °C (115 °F) during the summer and −5 °C (23 °F) during winter. UV levels are extreme between October and March, averaging between 11 and 15 on the UV index.

Local Aboriginal people recognise five seasons:

- Wanitjunkupai (April/May) – Cooler weather

- Wari (June/July) – Cold season bringing morning frosts

- Piriyakutu (August/September/October) – Animals breed and food plants flower

- Mai Wiyaringkupai (November/December) – The hot season when food becomes scarce

- Itjanu (January/February/March) – Sporadic storms can roll in suddenly

Aboriginal myths, legends and traditions

According to the Aß╣ēangu, traditional landowners of Uluru:

The world was once a featureless place. None of the places we know existed until creator beings, in the forms of people, plants and animals, traveled widely across the land. Then, in a process of creation and destruction, they formed the landscape as we know it today. Aß╣ēangu land is still inhabited by the spirits of dozens of these ancestral creator beings which are referred to as Tjukuritja or Waparitja.

There are a number of differing accounts given, by outsiders, of Aboriginal ancestral stories for the origins of Uluru and its many cracks and fissures. One such account, taken from Robert Layton's (1989) Uluru: An Aboriginal history of Ayers Rock, reads as follows:

Uluru was built up during the creation period by two boys who played in the mud after rain. When they had finished their game they travelled south to Wiputa ... Fighting together, the two boys made their way to the table topped Mount Conner, on top of which their bodies are preserved as boulders. (Page 5)

Two other accounts are given in Norbert Brockman's (1997) Encyclopedia of Sacred Places. The first tells of serpent beings who waged many wars around Uluru, scarring the rock. The second tells of two tribes of ancestral spirits who were invited to a feast, but were distracted by the beautiful Sleepy Lizard Women and did not show up. In response, the angry hosts sang evil into a mud sculpture that came to life as the dingo. There followed a great battle, which ended in the deaths of the leaders of both tribes. The earth itself rose up in grief at the bloodshed, becoming Uluru.

The Commonwealth Department of Environment's webpage advises:

Many...Tjukurpa such as Kalaya (Emu), Liru (poisonous snake), Lungkata (blue tongue lizard), Luunpa (kingfisher) and Tjintir-tjintirpa (willie wagtail) travel through Uluß╣¤u-Kata Tjuß╣»a National Park. Other Tjukurpa affect only one specific area.

Kuniya, the woma python, lived in the rocks at Uluru where she fought the Liru, the poisonous snake.

It is sometimes reported that those who take rocks from the formation will be cursed and suffer misfortune. There have been many instances where people who removed such rocks attempted to mail them back to various agencies in an attempt to remove the perceived curse.

History

Archaeological findings to the east and west indicate that humans settled in the area more than 10,000 years ago. Europeans arrived in the Australian Western Desert in the 1870s. Uluru and Kata Tjuta were first mapped by Europeans in 1872 during the expeditionary period made possible by the construction of the Australian Overland Telegraph Line. In separate expeditions, Ernest Giles and William Gosse were the first European explorers to this area.

While exploring the area in 1872, Giles sighted Kata Tjuta from a location near Kings Canyon and called it Mount Olga, while the following year Gosse observed Uluru and named it Ayers Rock, in honour of the Chief Secretary of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers. Further explorations followed with the aim of establishing the possibilities of the area for pastoralism. In the late 19th century, pastoralists attempted to establish themselves in areas adjoining the Southwestern/Petermann Reserve and interaction between Aß╣ēangu and white people became more frequent and more violent. Due to the effects of grazing and drought, bush food stores became depleted. Competition for these resources created conflict between the two groups, resulting in more frequent police patrols. Later, during the depression in the 1930s, Aß╣ēangu became involved in dingo scalping with 'doggers' who introduced Aß╣ēangu to European foods and ways.

Between 1918 and 1921, large adjoining areas of South Australia, Western Australia, and the Northern Territory were declared as Aboriginal reserves, sanctuaries for nomadic people who had virtually no contact with European settlers. In 1920, part of Uluß╣¤u–Kata Tjuß╣»a National Park was declared an Aboriginal Reserve (commonly known as the South-Western or Petermann Reserve) by the Australian government under the Aboriginals Ordinance.

The first tourists arrived in the Uluru area in 1936. Beginning in the 1940s, permanent European settlement of the area for reasons of the Aboriginal welfare policy and to help promote tourism of Uluru. This increased tourism prompted the formation of the first vehicular tracks in 1948 and tour bus services began early in the 1950s. In 1958, the area that would become the Uluß╣¤u–Kata Tjuß╣»a National Park was excised from the Petermann Reserve; it was placed under the management of the Northern Territory Reserves Board and named the Ayers Rock–Mount Olga National Park. The first ranger was Bill Harney, a well-recognised central Australian figure. By 1959, the first motel leases had been granted and Eddie Connellan had constructed an airstrip close to the northern side of Uluru.

On 26 October 1985, the Australian government returned ownership of Uluru to the local Pitjantjatjara Aborigines, with one of the conditions being that the Aß╣ēangu would lease it back to the National Parks and Wildlife agency for 99 years and that it would be jointly managed. An agreement originally made between the community and Prime Minister Bob Hawke that the climb to the top by tourists would be stopped was later broken. The Aboriginal community of Mutitjulu, with a population of approximately 300, is located near the eastern end of Uluru. From Uluru it is 17 km (11 mi) by road to the tourist town of Yulara, population 3,000, which is situated just outside the national park.

On 8 October 2009, the Talinguru Nyakuntjaku viewing area opened to public visitation. The A$21 million project about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) on the east side of Uluru involved design and construction supervision by the Aß╣ēangu traditional owners, with 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) of roads and 1.6 kilometres (1 mi) of walking trails being built for the area.

Tourism

The development of tourism infrastructure adjacent to the base of Uluru that began in the 1950s soon produced adverse environmental impacts. It was decided in the early 1970s to remove all accommodation-related tourist facilities and re-establish them outside the park. In 1975, a reservation of 104 square kilometres (40 sq mi) of land beyond the park's northern boundary, 15 kilometres (9 mi) from Uluru, was approved for the development of a tourist facility and an associated airport, to be known as Yulara. The camp ground within the park was closed in 1983 and the motels closed in late 1984, coinciding with the opening of the Yulara resort. In 1992, the majority interest in the Yulara resort held by the Northern Territory Government was sold and the resort was renamed Ayers Rock Resort.

Since the park was listed as a World Heritage Site, annual visitor numbers rose to over 400,000 visitors by the year 2000. Increased tourism provides regional and national economic benefits. It also presents an ongoing challenge to balance conservation of cultural values and visitor needs.

Admission

Admission to the park costs A$25 per person and provides a three-day pass. Passes are non-transferable and all passes are checked by park rangers.

The Aboriginal traditional owners of Uluß╣¤u–Kata Tjuß╣»a National Park (Nguraritja) and the Federal Government's National Parks share decision-making on the management of Uluß╣¤u–Kata Tjuß╣»a National Park. Under their joint Uluß╣¤u–Kata Tjuß╣»a National Park Management Plan 2010–20, issued by the Director of National Parks under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, clause 6.3.3 provides that the Director and the Uluß╣¤u–Kata Tjuß╣»a Board of Management work towards closure of the climb and, additionally, provides that it will close upon any of three conditions being met: there are "adequate new visitor experiences", less than 20 per cent of visitors make the climb or the "critical factors" in decisions to visit are "cultural and natural experiences". Despite cogent evidence the second condition was met by July 2013, the climb remained open.

Several controversial incidents on top of Uluru in 2010, including a striptease, golfing and nudity, led to renewed calls for banning the climb.

On 1 November 2017, the Uluß╣¤u–Kata Tjuß╣»a National Park board voted unanimously to prohibit climbing Uluru, with the ban to take effect in October 2019.

Geography

Situation and description

Uluru is located southwest of the Northern Territory, in the heart of the Australian outback, in the national park of Uluru-Kata Tjuta, near the small town, similar to a tourist complex, 335 km as the crow flies southwest of Alice Springs and Yulara (440 km by) the road). There a height of 348 meters, from the ground and an altitude of 863 meters over the sea level although he sinks deep underground. It has a perimeter of 9.4 km and 2.5 km long. The rock formation of Kata Tjuta is located 25 kilometers from Uluru.

An aerodrome (Connellan airport, IATA code: AYQ, ICAO code: YAYE) serves the site. Car parks and access roads were also built to provide views for tourists.

Uluru is one of the symbols of the Australia. It has a great cultural significance for the Anangu. One of its features is to change color in appearance depending on the light that illuminates it throughout the day and the year. The sunsets are particularly remarkable when they dye it briefly in red. Although the rains are rare in this arid region, it becomes grey silver during the wet periods due to the formation of black algae along the natural chutes of flow of the water.

Hydrography

The Anangu consider that all the aquifer sources in the park are the work of Tjukurpa. Knowledge of their location and sustainability has historically been an essential component of Aborigines' ability to survive by traveling through these lands.

The Mutitjulu source, at the base of Uluru, is considered to be the only permanent park source. It is powered by one of the Park's two underground water systems. After the rains, which occur irregularly, water can stay present more or less in the mares, at the level of the top of the rock, and flow channels forming gullies. The natural environment has a capacity of very fast regeneration after every heavy rain. Then, the water seeps into the basement and fills the groundwater.

Geology

Geomorphology

Uluru is often described as a monolith, but it is actually the emerged part of a rock formation of the basement cleared by erosion. The geomorphological point of view, it is an inselberg, an "Island mountain". It is the second largest worldwide, after mount Augustus, also in Australia.

A feature of Uluru is its petrographic homogeneity and a virtual absence of jointing surface, resulting in extreme weakness of scree on the slopes and at the base of the relief. These features have allowed sustainability, while the surrounding rocks were ironed out. The study of the relationship between inselbergs - Uluru and Kata Tjuta - terrain and Lake deposits of age Paleocene of the plain, in more humid climates, shows that these reliefs relictual practically retained the same contours and look the same since 60 million years and the levelling surface that they dominate is probably older.

Orogeny

The Mutitjulu arkose would be approximately the same age as the Kata Tjuta conglomerate and would have a similar origin despite a different type of rock. On the other hand, it is newer and unrelated to the tabular rock formation named Mount Conner, 88 kilometers to the east. The stratum that forms Uluru is practically vertical, with an 85 ° dip to the southwest and an apparent thickness of at least 2,400 meters. It sinks deeply under the surrounding plain, but its extent is unknown. The rock that formed it was the origin of the sand of a large cone of excrement that led down the chains of Mann and Petermann, the "ancestors" of the Musgrave Mountains, towards the north and east. It was close to another dejection cone made of sand, pebbles and stones that now constitutes Kata Tjuta. This explains the Mineralogical similarity between the arkose of Mutitjulu and granitic mountains eroded in the South. They were formerly a massive wide, raised during the Petermann orogeny that took place from the end of the Neoproterozoic-early Cambrian (550-530 my), time during which may have formed the Mutitjulu arkose. The granulometric composition of the sandstone shows a rapid erosion of the granites. The layers of sand were relatively horizontal when deposited at the level of the alluvial cone then have switched almost to the portrait during a subsequent tectonic phase, probably the orogeny of Alice Springs during the Paleozoic (400-300 my). Over time and erosion, the mountains became more and more low dunes, their sand tumbling and raising the ground level. This in addition to major flooding: waters were polite, buried under the sand, then retreating shaped these landscapes. Only Uluru is emerging today.

Petrology

To describe the geological history of the area, geologists call the stratum that constitutes Uluru Mutitjulu Arkose, one of the many sedimentary formations composing the basin of Lake Amédée. Uluru is mainly composed of coarse arkose, a type of sandstone characterized by its abundance of feldspar, and some conglomerates. The average composition consists of 50% feldspars, 25 to 35% quartz and up to 25% rock fragments. Most of the feldspars are orthoses with some plagioclases as angular grains and altered inclusions. The grain is generally 2 to 4 mm in diameter. The finest sandstone is well sorted, with distribution reducing the size of the grains. The rock fragments include the basalts, replaced to various degrees by chlorite and the epidote. The minerals present suggest a migration from a granitic source predominant, similar to the Musgrave Block in the South. The healthy rock has a grey color, but exposed to the meteoric agents, the degradation of ferrous minerals by oxidation gives the outer layers of the rock a rusty, red-brown hue. Sedimentation induced cross-stratifications and wavy rock formations due to deposits in shallow and high current streams, typical of alluvial fans.

Climate and seasons

The park receives an average of 330,5 mm of precipitation per year and average temperatures range from 37.5 ° C for the maximum in the summer to 3.4 ° C for the minimum in winter. The records recorded in the Park are 45 ° C in summer and −5 ° C on a winter night. The ultraviolet radiation is generally very strong on the Park.

The aborigines divide the year into five seasons:

1 Piriyakutu (August/September/October), breeding animals and plants flowering periods;

2 may Wiyaringkupai (October/November/December), hot season where food becomes rare;

3 Itjanu (January/February/March), sporadic storms can suddenly break out;

4 Wanitjunkupai (April/May), the temperatures are lower.

5 Wari (June/July), cold season with morning frosts.

Fauna and flora

Forty-six species of native mammals living in the Uluru region decades ago. The final checks indicate that there are twenty-one left. Reintroduction trials are underway for locally extinct species such as the Fox Phaler, Western Wallaby Hare, Bilby, Lesueur Bettongie and Rock Wallaby. This area is also home to the marsupial mole. There are seven bat species in the region that shelter during the day in the caves and cracks of Uluru and Kata Tjuta. Most bats feed on prey caught in flight within a 100-meter radius of the rock. One species of Dasycercus, the only mammal in the region considered to be endangered, has a very small area, a narrow strip of land that extends from the neighborhood of Uluru to the northern edge of the park.

The Park is home to a large amount of reptiles; seventy species are identified. The python of Ramsay and the great desert skink are considered to be vulnerable.

Four species of frogs are abundant in the region after the summer rains.

The avifauna is moderately rich but typical of arid environments. 178 species of birds have been recorded, including several rare: the splendid parakeet (Neophema splendida), the striated amytis (Amytornis striatus), or the White miners (Conopophila whitei). They are dependent on the presence of water, and many have a migratory behavior. Their habitat is shared between rocky cliffs, trees and bushes, ponds and channels, and grassy and sandy soils. Ocellated Leipoa, locally extinct, is being reintroduced.

The Anangu aborigines of the Park continue to hunt on the edge or outside the Park. Hunting is limited to the Red Kangaroo, to the Australia Bustard, EMU, Gould Lizard and Perenti Lizard.

Of the twenty-seven species of mammals found in the park, six were imported by Europeans: the mouse, camel, fox, cat, dog and rabbit. These species are found throughout the park but their density is higher near the water points.

Flora in Uluru-Kata Tjuta national park is made up of most of the species of the Australia Centre. Many of them are rare or endemic of the park or its neighbourhood. They can be classified according to the three layers of vegetation. Among the trees (punu) are Acacia aneura (the common mussel in Australia), Allocasuarina decaisneana, Codonocarpus cotinifolius, Corymbia terminalis, Eucalyptus camaldulensis and Eucalyptus gamophylla; bush species (puti) are represented by Grevillea eriostachya, Acacia kempeana and Eremophila latrobei; finally, the herbaceous plants are distinguished into flowers (ejulpun-tjulpunpa) and herbs (ukiri) according to the aboriginal classification and are composed in particular of Ptilotus obovatus, Ptilotus exaltatus, Thryptomene maisonneuvei and Crotalaria cunninghamii, Triodia basedowii, Triodia pungens, Eragrostis eriopoda, Paractaenum refractum and Panicum decompositum.

The growth and reproduction of the park's vegetation are dependent on the rains, which are very irregular. Some plants are able to resist fire (pyrophile species) and some of them are dependent on it to reproduce. Plants play an important role in Aboriginal legends (Tjukurpa) and many of them are associated with ancestors.

Trees such as the mulga and Corymbia terminalis, "blood tree", are used to make tools such as Spears, boomerangs and bowls. The Red SAP of the Corymbia terminalis is locally used as a disinfectant and as a mouthwash to treat colds and respiratory infections. Other plants are used for their nectar, as equivalent of tobacco, as building material for their adhesive properties, such as fuel or fuel or as an ornament.

There are several species of plants at risk in the Park. Most of them, like those kind of Ophioglossum, only grow in wet areas at the base of the rocks, those who are trampled by visitors.

Since the Europeans arrived, 34 exotic plants have been introduced in the Park, representing 6.4% of all of the flora of the Park. Some, such as Cenchrus ciliaris, were introduced to rehabilitate areas damaged by erosion. It is the most invasive species of the Park which tends to colonize all wet areas. Other species have been imported accidentally by vehicles or visitors.

History

Archaeological discoveries in the East and in the West of Uluru indicate the presence of human settlements in the area more than 10,000 years ago. The Europeans arrived in the Australian Western desert in the 1870s. Kata Tjuta and Uluru are mapped for the first time on the occasion of the expeditions as part of the construction of the trans-australian telegraph line. 1872 Ernest Giles observes, from a point near Kings Canyon, the site of Kata Tjuta, which he named mount Olga. He can't surrender on the spot, helmed by Lake Amadeus. The following year, William Gosse visit Uluru and gives him the name of Ayers Rock.

Later expeditions are organized in order to assess the possibilities of pastoral activities in the region. At the end of the 19th century, breeders are trying to settle on the edge of the South western/Petermann Reserve; the interactions between the Aß╣ēangu and white multiply and became more violent. Because of the pasture and the drought, the bush food reserves are running out. The competition for resources generates conflicts between the two populations and leads to increased of police patrols. Later, during the depression of the 1930s, Aß╣ēangu will be involved in hunting dingoes with the doggers who will introduce them to Western food and lifestyles.

Between 1918 and 1921, large adjoining areas of South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory were classified as aboriginal reserves, providing sanctuaries for nomadic populations that had virtually no contact with the settlers. Thus, in 1920, part of the current Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park was officially declared aboriginal reserve by the Australian Government by Aboriginal decree.

The first tourists arrived at Uluru in 1936. The first permanent facilities are built in the 1940s in agreement with the Aboriginal development policy and in order to promote tourism. The first road tracks are drawn in 1948 and a bus tour service is set up in the early 1950s. In 1958, the area corresponding to the current national park was withdrawn from reserve Petermann, placed under the leadership of the Northern Territory Reserves Board and named Ayers Rock - Mount Olga national park. The first ranger of the Park is Bill Harney, a personality recognized in the center of the Australia. In 1959, the first lease for the establishment of a motel was granted and Eddie Connellan built an airstrip North of Uluru.

On the 5th of March 1968, a three-seat Bell 47 G2 helicopter, piloted by Philip Latz, crashed on the mountain, one and a half kilometers east of the kairn. The wreckage is cleared on March 28 by a Sikorsky S-58 helicopter.

On October 26, 1985, the Australian Government surrendered the ownership of Uluru to the Pitjantjatjara Aborigines, with a condition that the Aß╣ēangu grant a 99-year lease to the National Parks and Wildlife Agency and that they manage the mountain coordinate. The community of Mutitjulu, estimated at 300 people, is located near the western slope of Uluru. Seventeen kilometers separate it, by road, from the tourist town of Yulara, populated by 3,000 inhabitants and located just outside the national park.

Activities

Tourism

Equipment

The development of tourism infrastructure at the foot of Uluru that began in the 1940s has quickly caused environmental damage. For this reason, it was decided in the early 1970s to move all facilities outside the Park. In 1975, a field of 104 km2 beyond its northern border, 15 km from the rock, was awarded to host and allow the development of childcare facilities and the construction of an aerodrome. This place definitely opened in 1984, was called Yulara. Campground within the Park has been closed to turn in 1983, followed by the motels at the end of the year 1984. In 1992, the majority of the properties of Yulara, held by the Government of the Northern Territory, was sold and the station was renamed Ayers Rock Resort.

A cultural center allows the discovery of traditions, legends, language and history of the aborigines. It was built of local materials (mainly of mud bricks) and its architecture, awarded in 1996, was inspired by two snakes Kuniya and Liru. Rangers are discovered the Park. Several circuits of one to 10 kilometers (3-4 hours 30 minutes) allow to discover Uluru, geological peculiarities, its water, its wealth of fauna and paintings.

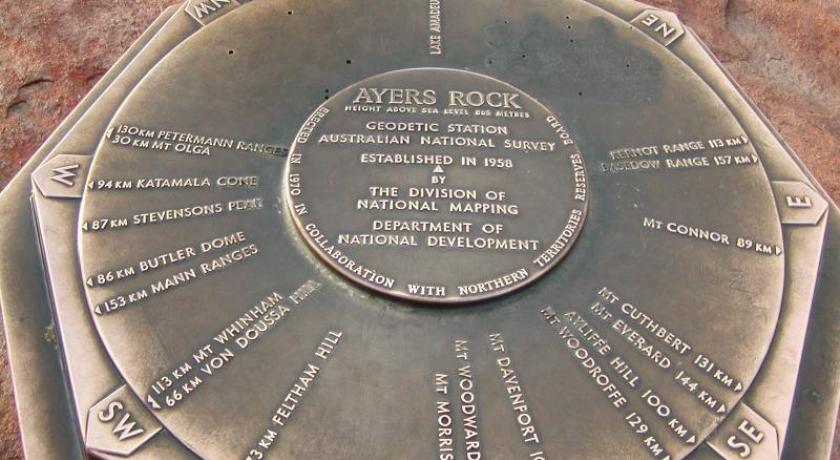

Ascension

The ascent of Ayers Rock is a popular attraction. It follows a path of 1.6 kilometers. The climb is long (over an hour of climbing) and is not easy because the slope varies from 30 to 60 degrees in some places, the weather can be difficult and the rock slippery. The handrail, a chain added in 1964 and lengthened in 1976, indispensable in places, allows an easier ascension. But accidents, sometimes fatal (35 known deaths in total), are numerous. At the top of the rock, extremely windy, is a plaque that identifies the surrounding mountains up to 157 kilometers away.

The rock being sacred to the aborigines, the Anangu themselves do not climb it. In addition, his ascension is strongly discouraged for those who are concerned to respect their beliefs, especially as the path leading to the summit goes through a traditional sacred track called "Time to dream". The severity of the ancestral Aboriginal laws can lead the latter to violent behavior towards their own person (self-mutilation, scarification, etc.) in the case of desecration, or even accident (due to the wind). In order to avoid these consequences, it is advisable for visitors to enjoy the rock in walking around.

On the 11th of December 1983, the Prime Minister Bob Hawke also promised, in its plan in ten points concerning the handover of Uluru to the Anangu, the prohibition of ascension. This condition has not been met. In October 2017, Uluru-Kata Tjuta national park Council voted unanimously for a total ban on the ascent of the mount Uluru from October 26, 2019, being the date of the 34th anniversary of the return of the mount under the control of the aborigines.

Photography

The monolith of Uluru is a sacred site of the aborigines, they have him great respect, and while their rituals remain secret, we know that two sites of Uluru are of high religious importance: one for women, one for men the most introduced, who converge by the hundreds in rare ceremonies. These two sites in particular are forbidden to photography, so that the Anangu are not aware of the rituals of the opposite sex.

Environmental protection

On the 24th of May 1977, the national park was the first place under the supervision of the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975, signed by the States of the Commonwealth of Nations. Its area covers 132 550 hectares and includes the underground on 1,000 meters of depth. On October 21, 1985, 16 ha were added. It was in 1993 that its current name was adopted: Uluß╣¤u-Kata Tjuß╣»a national park. In July 2000, it passes under the guardianship of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act.

Since the Park was ranked among the natural sites of the world heritage by UNESCO in 1987, the number of visitors has increased up to more than 400,000 a year since 2000. While the increase in tourism is primarily at the regional and national economy, it also presents a challenge for the conservation of the cultural heritage of the site. With this in mind, it was classified at the same time cultural site by UNESCO in 1994.

Popular culture

Myths of the creation of the world

Like many cultures, that of the aborigines of Australia, by attributing to certain places powers or a particular symbolism, conceived a sacred geography. According to their tradition, the beings of the "Dream Time" have shaped the forms of the world. Uluru is one of them. The rock is one of the points of the path traveled by the ancestors at the time of the dream, period of the formation of the world. This path is traveled annually by various tribes to perpetuate the memory and stimulate the spirits.

According to the indigenous Anangu of Uluru:

"The world was once formless, None of the places we know existed until creators, in the form of humans, plants or animals, travel through the Earth. Then, in a process of creation and destruction, they formed the landscapes that we know today. The Anangu land is still inhabited by the spirits of dozens of these Aboriginal creators who are called Tjukuritja or Waparitja. »

There are different interpretations given by foreigners to the Aboriginal ancestral stories regarding the origin of Uluru, its flaws and its cracks. It would have been built in Dream Time (Tjukurpa). Its isolation in the plain and the violence of the storms that attracted its mass make it a mythical place of reference. One of these interpretations suggests that:

"Uluru (Ayers Rock) was built during the creation period by two boys who were playing in the mud after rain. When they had finished playing, they traveled to the South to Wiputa. Fighting against each other, they made their way to Conner's tabular mount, on top of which their bodies are preserved in the form of rocks. "

Another interpretation speaks of snakes that led to many wars around Uluru, notching the rock, while another tells that two tribes of ancestral spirits, invited to a party but distracted by the beauty of the Tiliqua Woman, their commitments; in response, the angry guests summoned Evil in a mud statue that came to life in the form of a dingo. A great battle ensued, which ended with the death of the leaders of the two tribes. The earth itself rose in tribulation at the carnage, creating Uluru. It is the central place of beliefs of Anangu, for whom the rainbow serpent Yurlungur sleeps in one of the basins of the summit. All around this rock, many sites are sacred and bearers of memory and legends..

The Environmental Department provides the following advice and warnings:

"Many Tjukurpa such as Kalaya (EMU of Australia), Liru (poisonous snake), Lungkata (tiliqua), Luunpa (Kingfisher) and Tjintir-tjintirpa (the fantail hochequeue) travel through Uluru-Kata Tjuta national park. Other Tjukurpa affect only a specific area.

Kuniya, the python of Ramsay, lived in the rocks of Uluru where she fought the Liru, the poisonous fish. »

It is sometimes reported that those who take rocks from Uluru will be cursed and suffer misfortune. There are many cases where people have returned by parcel post to various agencies the rocks they had taken in the hope of getting rid of the woes affecting them.

Using of the name and popular references

In 1987, Midnight Oil, the rock band of the future Australian Minister of environment Peter Garrett, known for his activism for the Aboriginal cause, made the clip of their song The Dead Heart at the foot of Uluru. This set was also used in Fred Schepisi's film A Scream in the Night, released in 1988.

The asteroid (9485) Uluru was named after the monument.

In the literature, an episode of the cartoon Sandy and Hoppy is titled Ayers Rock and the Stone Monster on the cover of 9th Wonders! Heroes series is called Uluru. In the video game, Uluru is the name of a Lost Eden Valley.

In Australia, according to the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, any commercial use of the image of Uluru requires a permit.

Source: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uluru

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uluru

Address

Petermann

Australia

Lat: -25.344879150 - Lng: 131.032501221